Coffee’s history includes examples of shops and cafes that didn’t fit their historical context. On this episode of Coffee Canon, we deep-dive into one of these; a shop that was opened in 1919, but bears a striking resemblance to modern artisan coffee shops. The Double R Coffee House was ahead of its time, and its owners bear a familiar, American name – Roosevelt.

This episode contains references to a wealth of sources and articles, which I’ve linked to below. Most notably, I ordered scans of the Library of Congress file titled “Double R Coffee House.” You can download the PDF here.

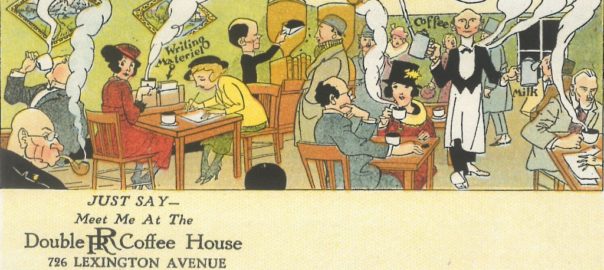

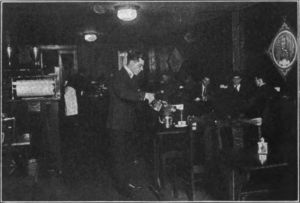

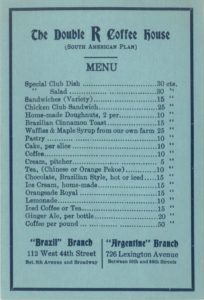

Below are a couple of images from The Double R Coffee House, some of which are discussed in this episode (click for full resolution versions):

Final note: Coffee Canon is now available on Spotify! Click here to listen, and make sure to click the “Follow” button!

Episode Nine Sources:

- “The Roosevelt Family Built a New York Coffee Chain 50 Years Before Starbucks,” Smithsonian Magazine, by Jancee Dunn.

- “Meet Me at the Double R Coffee House,” New-York Historical Society, by Edward O’Reilly.

- New York Times article announcing coffee shop opening (November 26, 1919): https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1919/11/26/96868990.pdf

- “All About Coffee” by William Ukers, 1922. Page 690 (769 of PDF) blurb about the coffeehouse while it was still open.

- Double R Coffeehouse mentioned in The Greenwich Village Quill (Magazine & Guide to Greenwich Village), August 1921 publication.

- Joshua Reyes, The Rough Writer: The News of the Volunteers at Sagamore Hill, Volume 9, Issue 3.

- “Simmons’ Spice Mill” VOL XLIII, dated January 1920. Page 56 (31 of PDF) blurb about the origins of the “Brazilian Coffee House” months after it opened.

- Wikipedia

- Philip Roosevelt (cousin of President Teddy Roosevelt) served as President of Double R Coffeehouse. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip_Roosevelt#cite_note-5

- Discussing Kermit Roosevelt and Teddy Roosevelt’s South American expedition in 1913-1914: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kermit_Roosevelt#River_of_Doubt_South_American_expedition

- HP Lovecraft blog that discusses him visiting the coffeehouse: https://tentaclii.wordpress.com/2011/08/12/lovecrafts-double-r-coffee-house-photo/

- “On The Double-R Coffee House” full poem by HP Lovecraft (1925): http://www.hplovecraft.hu/print.php?type=etexts&id=411&lang=angol

- Good source for Lovecraft info: https://img.4plebs.org/boards/tg/image/1372/86/1372867413177.pdf

- “Remembering the Sullivan County Catskills” section on Mrs. Elizabeth Worth Muller.

- Music

- “Climbing the Mountain,” Podington Bear http://freemusicarchive.org

- “Into the Unknown” Podington Bear http://freemusicarchive.org

- “A Gentleman” Podington Bear http://freemusicarchive.org

- “Sweet and Clean” Podington Bear http://freemusicarchive.org

- “Blues Angeline,” Lobo Loco http://freemusicarchive.org

Episode Nine Transcript:

Last episode, we talked about modern coffee culture, including what have become known as the “three waves” of coffee. While a rough construct, it does give a fairly good frame of reference when we talk about coffee’s history. It’s been a while since that episode aired, so here’s a quick recap: the first wave is associated with World War I and World War II, which brought coffee to the masses in pre-ground, airtight containers. The second wave was popularized with Starbucks and similar coffeehouses, which focused on quality above commodity, putting a larger emphasis on where coffee is grown and how it’s roasted. The third wave is associated with modern, artisan coffeehouses that are able to deal directly with farmers, care deeply about taste, and eagerly look for ways to push the craft of coffee forward. With all that said, it’s also important to realize that, like any aspect of culture, there are some people and stories that just don’t fit into their ‘wave.’

There are lots of modern examples of coffee companies that look and taste more like they belong in the first or second wave. One of these is Keurig – mass-produced, pre-ground coffee for everyone, even if that comes at the expense of quality, taste, or ecological sustainability. While fewer in number, there are also examples of people and coffee companies that were ahead of their time; they lived during the first or second wave, but acted like a modern, third wave company. On today’s show we’re going to deep-dive into one of these examples. The coffee shop we’re looking at today was opened in New York City in 1919. Its founders bear a familiar, American name – Roosevelt, and its origins start in the jungles of Brazil.

I’m Colin Mansfield, and welcome to Coffee Canon.

Four years after leaving office, the 26th President of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt, and his son Kermit went on an expedition to the Amazon Basin Brazilian jungle. The year was 1913, and the journey came to be known as the Roosevelt-Rondon Scientific Expedition. Together with explorer Colonel Cândido Rondon, the group would go on to map the River of Doubt, a completely uncharted river over 1000km long. Later, as a result of the expedition, it was renamed Rio Roosevelt. Kermit accompanied his father at the behest of his mother Edith – he was reluctant, because it meant delaying his marriage, but his mother’s concerns about Teddy Roosevelt’s health and the difficulties of a new expedition won him over.

Originally, the scope of the expedition was small. It quickly expanded beyond the group’s original plans, leaving them inadequately prepared to face the dangers of the jungle. Of the 19 men who departed on the expedition, 16 returned home. One died by accidentally drowning in river rapids, and one was murdered by another member of the group. The murderer was left in the jungle, where he presumably died. Teddy Roosevelt was nearly a fatality himself – he contracted malaria and a serious infection from a small leg wound. The former president was weakened to the point of considering to take a fatal dose of morphine rather than be a burden to his son and companions. Kermit told his father that he was bringing him back dead or alive – and if he died, he would be an even bigger burden to the expedition. Kermit contracted malaria as well, but he saved medicine for his father and downplayed his own sickness. This nearly killed him – he lived only because a physician took action and directly injected quinine into Kermit.

Kermit’s outdoorsmen skills and determination saved his and his father’s lives. The expedition concluded in 1914, after which the group returned home. Kermit married his wife Belle, and he started his next job: assistant manager of the National City Bank in Buenos Aires, Argentina. He worked in that position from 1914-1916. By that time Kermit was very familiar with the culture of South America, and he became intrigued by the region’s coffeehouses. Where, in the United States, coffee was served quickly and drunk with haste, in South America it was made with freshly ground beans, and consumed leisurely, in a relaxed environment. Kermit Roosevelt saw a business opportunity. He conceived an idea to start a coffee house in the United States modeled after those he experienced in South America, and he pitched the idea to his brothers. But then, in 1917, the US entered World War I. Kermit’s idea was put on hold until after the war, at which point he brought it up again.

On January 29, 1919 the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution was certified and ratified, prohibiting the production, transport, and sale of alcohol nation-wide. The National Prohibition Act, also known as the Volstead Act, was passed in the the US Congress over President Woodrow Wilson’s veto on October 28, 1919. One month later, almost to the day, the New York Times ran an article: “Roosevelts Start Coffee House Chain. Houses Similar to the Ancient Institutions of London to be Established. Six relatives in the firm. Not restaurants, but similar to Paris Coffee Houses – first one is now open.”

Philip Roosevelt, a cousin of Teddy Roosevelt, was the president of the venture. He shared ownership equally with the Roosevelt children: Kermit, Archie, Ted, and Ethel, along with her husband Richard Derby. Together, their goal was to combine Kermit’s vision of a relaxed South American coffee house with the class and professionalism of a Parisian cafe. Their first store was named the “Brazilian Coffee House.” Their mission is perhaps best summed up by Philip Roosevelt. “What we desire to do,” he told a reporter, “is to provide a place for people to come, where they can talk write letters, eat sandwiches and cake, and above all, drink real coffee.”

While the Roosevelts knew how to start a business, they knew next to nothing about running the daily operations of a coffee shop. To help with this, they hired a Brazilian man named Alfredo M. Salazar who was well-versed in coffee house operations, having previously managed a shop. His attitude and approach to running the coffee shop is best characterized in the following quotes, taken from the New York Times announcement of the Brazilian Coffee House’s grand opening:

Salazar said, “We are not a restaurant; please make that clear. The law required that we incorporate as a restaurant, but we are a coffee house, a real coffee house, like those in London several centuries ago, and similar to the ones at present in Paris and cities in Brazil. We do not serve food enough to be classed as a restaurant, only a little pastry and sandwiches with our coffee. Every day, also, we have on the menu a Brazilian dish for such persons as want a light lunch.” He goes on to say, “But it is coffee in which we are mainly interested, and we will sell it to drink or to carry home. In the first place, the American people don’t really know how to appreciate good coffee. They prepare it either in the percolator or by boiling. We make it like tea, by pouring boiling water over coffee through a specially prepared strainer. We are willing to show any one who desires to learn how to roast and prepare the coffee in the real Brazilian manner. In this connection I would say that in America the tendency is not to roast the coffee sufficiently. To serve poorly roasted coffee is injurious to the health, as only by roasting can the poison – caffeine – be eradicated.”

Calling Alfredo Salazar passionate is a massive understatement – the man was emphatic about his opinions on coffee. I think he would feel quite at home with modern bohemians, discussing what *real* coffee tastes like. The last sentence regarding caffeine is interesting – especially given a sign that hung outside the coffeehouse. It read “If Postum disagrees with you, try a cup of our coffee.” Postum is a roasted grain-based beverage which was a popular coffee substitute in early 20th century. It was considered safe to those who feared the effects of caffeine. Caffeine fear-mongering aside, it’s easy to draw connections between present-day coffee fanatics and The Brazilian Coffee House’s manager.

According to the January 1920 issue of Simmons’ Spice Mill – a periodical that discussed the spice, tea, and coffee trades – the Brazilian Coffee House was located in the geographical center of the theatrical district of New York City. This helped the business get off to a great start – even better than the Roosevelts had hoped for. The article goes on to say “In planning the decorations, one of the partners chanced to remember that Voltaire has been credited by historians with drinking no less than seventy-five small cups of coffee each day, and that Shakespeare wrote: ‘Coffee, thou art all the comfort the gods will diet with me.’ As an effort is to be made to draw no small proportion of the establishment’s patronage from the literati of the city, portraits in color of Shakespeare and Voltaire have been placed conpicuously upon the walls, together with a work of art depicting the harbor of Rio de Janeiro, the capital of the country from which the greater part of the coffee comes.”

According to Janesville Daily Gazette, Ethel Roosevelt – one of the Roosevelt children – was responsible for interior decorating at the coffee house. The shop was long and narrow; when patrons first entered, they were greeted by the portraits of Voltaire and Shakespeare on opposite sides of the room. Green and gold wallpaper covered each wall, featuring a Brazilian bamboo plant design. The room itself was adorned with 30 small oak tables and matching chairs. These were no ordinary tables – each had a compartment containing ink, envelopes, and paper inscribed with “Brazilian Coffee House.” Dictionaries and encyclopedias were available for patrons’ use as well. In effect, the Roosevelts had created a pre-technology internet cafe. Visitors could read, write, study, or draw – all while sipping on craft coffee.

Clearly the business was off to a great financial start. About $10,000 was invested in the outset. And if you think that sounds impressive, taking inflation into account, that’s about $125,000 in today’s money.

Shortly after the New York Times published their initial introductory article about the Roosevelts’ Brazilian Coffee House, a columnist wrote a follow-up editorial. They said, “The idea was hardly as original…as the originators seem to think…there have long been more than a few places on the east side…However, these older coffee houses have appealed chiefly to what is called the foreign element.” They went on to say, regarding Prohibition, “the time is favorable for the starting of something that will or may bring men together in the sort of sociability which was for many not the least attraction of the vanishing saloon.” Many of the sources I read indicated a similar sentiment: the Roosevelts’ coffee house came at the right time – a sort of flagship coffee shop experience beckoning to those who previously found their social home in bars. That same Janesville Daily Gazette article I mentioned earlier put it bluntly: “New York has to thank Prohibition for one blessing, and that is the establishment of a modern coffee house, where it is possible to obtain a cup of coffee that is coffee and not tannic acid soup. It also has to thank the Roosevelt family…[for its] new and picturesque enterprise.”

In 1921 the Brazilian Coffee House had to change its name. Our passionate friend Alfredo Salazar, as it turned out, had once owned a coffee house by the same name (you would’ve thought he could have brought that up sooner). When he sold it, the new owners retained the rights to the name. After the positive press and fanfare that the Roosevelts’ Brazilian Coffee House received, these owners served legal notice and demanded a name change. Wanting to avoid litigation, the Roosevelts landed on a new name: The Double R Coffee House. The two Rs stood for Roosevelt and Robinson – for Monroe Douglas Robinson, a nephew of Teddy Roosevelt who had joined the venture as well.

When I begin researching for these podcast episodes, usually I start where most people would: Google searches, and Wikipedia. More than anything, I’ve found Wikipedia to be a great place to discover primary source documents and articles. My research for this episode brought me back to one familiar source – William Ukers’ book “All About Coffee,” which I’ve referenced on previous episodes of the show. Another huge source was a Smithsonian Magazine article written in 2014 titled, “The Roosevelt Family Built a New York Coffee Chain 50 Years Before Starbucks.” Much of the historical narrative I’m exploring in this episode came from the timeline laid out in that article, but it also pointed me to another key source of information: Mr. Joshua Reyes. Josh is a National Park Service ranger at Sagamore Hill National Historic Site – the home of Theodore Roosevelt. Not only did he provide the Smithsonian Magazine with an interview for their piece, but he also was kind enough to respond to my emails and send me additional sources.

In March of 2007 Josh Reyes wrote a piece about the Double R in a newsletter to the volunteers at Sagamore Hill called “The Rough Writer.” The write-up gives some great information that I’ve already covered in this episode, specifically in regards to the layout of the Double R and what it looked like. At the end of the article, Josh wrote, “The coffee house was reportedly part of a chain, however, no supporting evidence for this has been found. The Kermit and Belle Roosevelt papers, located at the Library of Congress, have a file labeled the Double “R” Coffee (Box 118). It is quite possible this may contain the missing pieces to this story.”

This piqued my interest – the Library of Congress, after all, is accessible to the public and has an online presence. Using this information, I started searching the Library of Congress database for this file. I was able to find the specific location of the file, but as it turns out, the Library of Congress doesn’t keep digital scans of everything on their website. Instead, I had to fill out a series of forms and pay a fee to request a scan of the file be made and sent to me. I sent in the required documentation last October, I received confirmation that there was a researcher assigned to my order in November, and finally – on December 20th – I was sent a link to the file. I’ve included it as a download in this episode’s show notes in case you want to take a look, but I’m going to cover it in detail over the remainder of the episode as well.

The file is fascinating. The first page is a letter dated September 11th, 1922 from Kermit Roosevelt to the U.S. Navy’s Bureau of Navigation. It reads:

“Dear Sirs: Chief Yoeman, Joseph P. Hetzler, submitted an application for discharge on September fourth from the Receiving Ship at Philadelphia. He is to enter the employ of the Double R Coffee House, with which I am associated, if his application is granted. If it is entirely in order it would be a great convenience to the Coffee House if this application were acted upon as speedily as circumstances would permit.”

The next dozen pages include correspondence between Kermit Roosevelt, Joseph Hetzler, a U.S. Navy Lietenant Commander named H.C. Gearing, and a Navy Commander named Frank Jack Fletcher regarding this job opportunity.

I’m not sure who Joseph Hetzler is; online searches didn’t turn up anything. I do know, however, what position he was vying for within the Double R.

In a 1922 letter to Mr. Patterson Way – a man who, based on other letters in the file, was involved with the finances for the Double R – Hetzler writes, “If my [US Navy] discharge does not come along within the next few days (or at least by the early part of next week) as a last resort I shall write a personal letter, enclosing copy of my request for discharge, to an officer in the Department who will follow it up from that end. There is so much “red tape” connected with the Service that one never knows how long such a request will take. I regret very much having to cause you all this trouble but I am sure you understand that it is only a matter of Navy routine and red tape which takes up so much time. I am looking forward to taking over the management of the Double R on Lexington Avenue upon my return and will strive my hardest to please you and Mr. Roosevelt.”

That last sentence is key. Whoever Chief Yeoman Joseph Hetzler is, this letter reveals a valuable piece of information – in 1922 the Double R did, indeed, have multiple branches. Or at least two: the Brazilian Location located on 44th Street, and another location on Lexington Avenue. I found two other sources that talk about this second Lexington Avenue branch. The first was a menu reportedly from the Double R. Both the Smithsonian Magazine article and a New-York Historical Society blog post included a scanned image of this menu within their writings. According to those articles, it comes from the Mildred & Philip Sawyer Papers – a collection of some 75 correspondence, notes, pamphlets, fliers, and other writings of Miss Mildred Sawyer and her father, architect Philip Sawyer of New York City. While I couldn’t view the papers themselves – the New-York Historical Society doesn’t offer digital access – I can verify that the documents were all from the years between 1895-1942. I think it’s safe to say this menu is legit.

The second source that talks about the Lexington Avenue branch is Ukers’ book “All About Coffee,” published in 1922. In it he writes “Members of the family of the late Colonel Roosevelt began to promote a Brazil coffeehouse enterprise in New York in 1919. It was first called Café Paulista, but it is now known as the Double R coffee house, or Club of South America, with a Brazil branch in the 40’s and an Argentine branch on Lexington Avenue.” The reference to the Double R being called “Café Paulista” stems from when the business was first incorporated in 1920. It appears as though the Roosevelt’s hadn’t yet finalized a name, and needed something to get the ball rolling.

According to the Smithsonian Magazine article, the Double R expanded beyond these two locations in the years that followed to four total coffee shops, all named after South American locations: the original Brazilian branch, an Argentine outpost, a Colombian, and an Amazon. Apparently at one point there were plans in the works to take the Double R brand national; Archie Roosevelt reportedly scouted sites in Chicago and planned other trips to Boston and Philadelphia for the same reason. We may never know why the Roosevelt children didn’t move forward with these plans – maybe they didn’t have the money to make it happen, or maybe – like with many projects the Roosevelt family started – they just decided to move on to something new.

Philip Roosevelt’s dream of creating a place for people to sit, write letters, talk, and drink great coffee came true. The placement of their flagship Brazilian location certainly helped – the theater district was exploding with writers and thinkers who wanted to be around like-minded people. Just about every major narrative I found regarding the Double R mention one particular patron who frequented the coffee house, and even wrote a poem about it – H.P. Lovecraft. The poem, titled “On The Double-R Coffee House,” is 7 stanzas long and ripe with descriptions of the shop and its frequenters. Here’s an excerpt:

“Amid the tap-room’s reeking air

Where smoky clouds and candles choke,

The choicest wit is said to flare,

And art to shed its daily cloak.

Here may free souls forget the grind

Of busy hour and bustling crowd,

And sparkling brightly mind to mind

Display their inmost dreams aloud.”

I couldn’t find many primary sources discussing why H.P. Lovecraft so enjoyed the Double R. I did find a well-researched paper, however, titled “Walking with Cthulhu: H.P. Lovecraft as psychogeographer, New York City 1924-26” by David Haden. Haden makes some interesting claims regarding the Double R, particularly regarding why it was so popular in Lovecraft’s literary circle, called the Kalem Club. Side note, the Kalem club got its name because the member’s last names all began with the letters K, L, or M. So, the more you know. One of the members of the Kalem Club, George Kirk, wrote a letter in 1925 mentioning the Double R. “If you had been longer in NYC you’d know that there are many boys and many girls both male and female. My dear Double-R is claimed to be the hangout for these half and halfers.”

Using this letter as a base, David Haden posits that the Double R was a popular discreet meeting place for gay men and women in the mid 1920s. This may have some truth to it – in 1925 police raids of gay clubs were normal, and the Double R would have been a natural meeting place.

According to the Smithsonian Magazine article on the Double R, in the late 20s the Roosevelts were moving on to other ventures. In 1928 Ted Jr. and Kermit were preparing for an expedition of Indochina to collect flora and fauna specimens – the largest of which was apparently a giant panda, which they shot and killed.

Interestingly, the Library of Congress papers I received include correspondence with coffee giant Maxwell House, dated May 20, 1927. There’s no confusion about the topic of discussion- the note is titled, “Memorandum regarding negotiations with the Maxwell House Coffee Company, concerning their possible purchase of the control of the Double R Coffee House.” The memorandum is interesting, and includes specific dollar amounts the Double R leadership would be willing to offer.

“I did not talk terms of purchase with Mr. Cheek, but Mr. Robinson, when I was not present, and given them to understand that we would consider selling fifty-one per cent for $15,000. In my opinion the purchase price would not be a matter of negotiation with them. In other words, I would not advocate naming a higher price and then be prepared to come down. I think that we should select a fair price and make them a firm offer, and that they will either take it or leave it. I do not believe that a few thousand dollars, one way or the other, will weigh very much with them. $15,000 seems to me to be a logical proposition, but if $16,000 makes the distribution of the indebtedness, or the transfer of the stock simpler, i think it is entirely feasible to ask it, at the same time explaining why you had picked upon that amount.”

It’s likely that Maxwell House was interested in purchasing the Double R because of the myth surrounding their slogan, “good to the last drop.” Maxwell House claimed that President Teddy Roosevelt declared this while visiting Andrew Jackson’s estate in 1907. There’s really no way to know for sure, and most sources seem to agree that the story is fabricated. But from the tone of the negotiations with Maxwell House, the Double R could have cared less – $15 grand is $15 grand.

For whatever reason, the sale never went through. Maxwell House bowed out. It was another year before the Roosevelt children sold the Double R. The final letters in the Library of Congress file I received include correspondence leading up to this sale – two notes from Mrs. Elizabeth Worth Muller. Mrs. Muller and her two daughters, Alma and Phyllis, were prominent suffragists in the early 1900s – Elizabeth was once arrested for picketing the White House regarding giving women the right to vote. She was an incredibly modern woman for the time, spearheading the Progressive Party in her local Sullivan County while Teddy Roosevelt championed the party nationally. According to one book I found, she was the first woman in her county to procure a big game hunting license. Her husband was a wealthy real estate mogul, and they had residences in Monticello, NY, Long Island, and Manhattan.

According to the Double R file, in December 1927 she wrote a letter to one of the Roosevelt children, likely Kermit. In the letter she argues to lease the coffee house to two individuals. “I only know their first names, the sister of the woman has been the most faithful housekeeper, and her husband an unusual butler, that I feel one is in luck to do business with them.” Regarding the lease, she writes, “…to my way of thinking is to collect one hundred dollars a month on the lease, to run it on a paying basis…and like all who work in that way, they take their share first, and there wouldn’t be a hundred left for you. That amount would be rather a good revenue on your investment, it will mean hard labor, work, and then work to get that place on a paying basis.”

Based on the context of this letter, it seems as though the Double R had fallen on hard financial times and poor management. This becomes even clearer in the final letter Mrs. Muller wrote to the Roosevelts. “I do so want my people to get the place before it is entirely hopeless. Every time I go there and see those wonderful portraits of your own blessed Father I get fighting mad. That place, to my own way of thinking, is a disgrace to the name of Roosevelt. I am convinced that $1,000 must be spent at once, the side walls all marked by head grease, floors unpolished, those coat chained chairs are 100 years out of date.”

She even gets specific, writing, “I took Virginia Ham and spinach last week. The ham was tainted. I sent it back. The second portion was even worse. If my protégées are to have the place, the sooner the better.” She ends the letter by naming the future owners. “I certainly would be happy to have the Magdichs get the place very soon to convince you that I have good judgement and faith in the right people, just as I did when I gave my very strength and life to the Progressive Party.”

The very last letter in the Double R Coffeehouse Library of Congress file is addressed to Mr. Z Magdich. It’s unsigned, but probably came from Kermit Roosevelt. In part, it reads, “Dear Mr. Magdich: My sister-in-law, Mrs. Theodore Roosevelt, is taking over the management of the Coffee House. She would like to see Mrs. Magdich and you at eleven o’clock on Monday morning at the house of her mother, Mrs. H. A. Alexander, #167 East 74th Street.” We don’t know what was discussed at this meeting, but it’s likely that it was the first step in transferring ownership to the Magdichs. Mr. Zivko and Mrs. Aneta Magdich bought the Double R in 1928, according to a New York Times article. Apparently one of the reasons the couple was so interested in owning the Coffee House was a romantic attachment – it was there that they had first met.

Little is known about what became of the Double R after 1928. But I think it’s safe to say that, like many businesses, it fell victim to the stock market crash of 1929 that signaled the beginning of the Great Depression.

The three waves of coffee are a great construct for discussing coffee’s progression from traded commodity to specialty beverage, but the reality is that coffee’s history is littered with examples like the Double R. It was a coffee house ahead of its time, not conforming to any one wave. And while the coffee house is, for all intents and purposes, forgotten today, it reminds us that there are some elements of human nature that are as true now as they were in the 1920s: people want a place to sit, enjoy a hot beverage, and share ideas. Kermit Roosevelt thought he was bringing a piece of South America back to the New York City, but in reality, he was re-introducing something that resonates with people of all backgrounds: a sense of community and belonging.

Thanks for listening to Coffee Canon. This episode has been a long time coming, and I hope you enjoyed it and learned something new. If you’d like to see pictures of the Double R, or download the Library of Congress file I referenced throughout this episode, check out the post on my website, BoiseCoffee.org. Also, if you haven’t done so already, follow Boise Coffee on Instagram. I post daily coffee humor, memes, and beautiful photos on my story there. Finally, I’m happy to announce that you can now listen to Coffee Canon on Spotify! Just search “Coffee Canon” and click the follow button. I hope to have more episodes up soon, but I also have a baby on the way – so no promises. Thanks again for listening, and have a great rest of your week.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Android | Stitcher | RSS